Taking care of urban microclimates through better design and greater energy efficiency

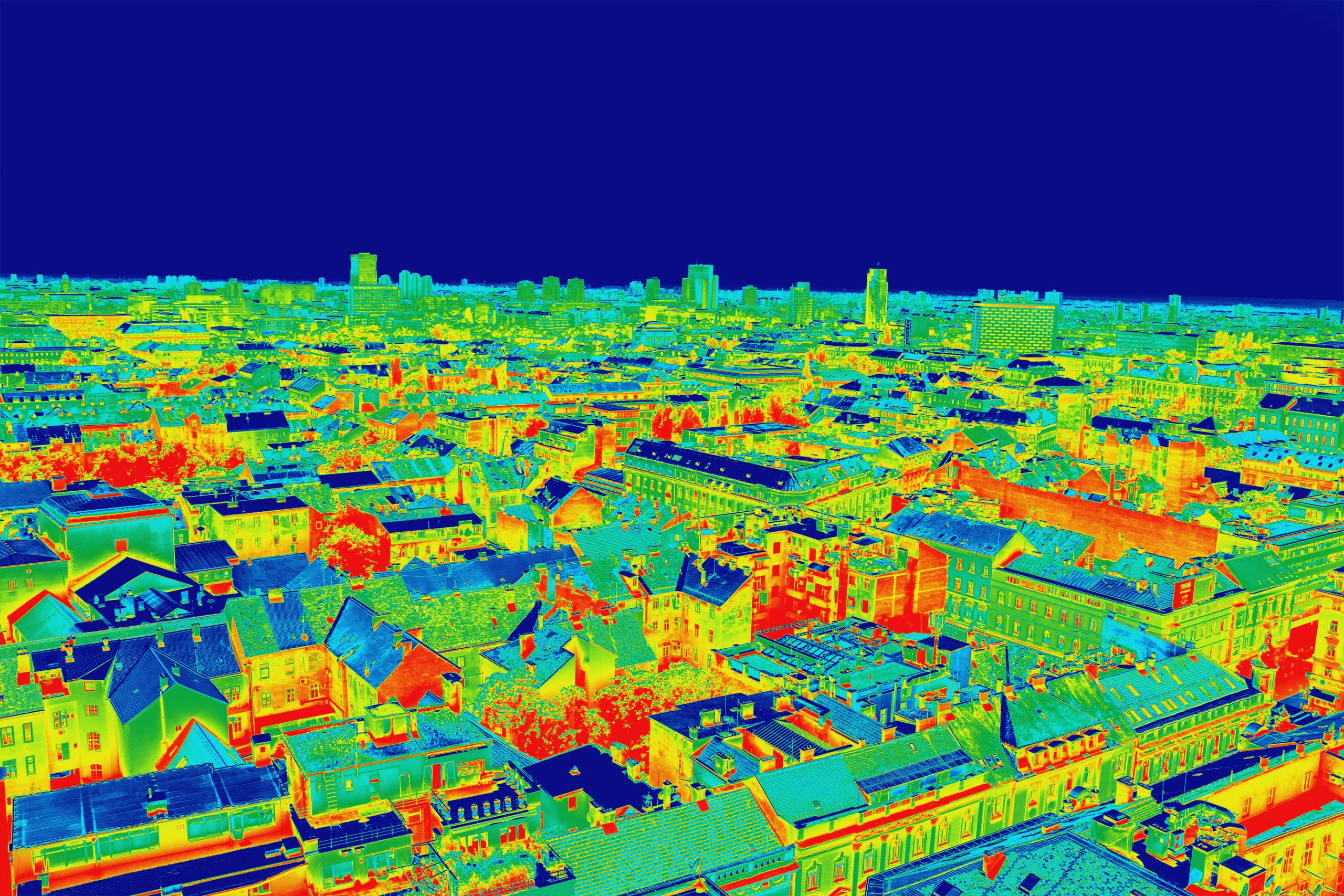

Microclimates are commonly found in nature. In cities, though, they are often seen as an unintended and undesirable consequence of urbanization – heat islands are the best known of these. But a new push in planning is changing how we think about urban microclimates, and what we do with them.

Gardeners and farmers have intentionally used microclimates for years to grow things where they otherwise couldn’t be grown. Meanwhile, cities have accidentally created microclimates like urban heat islands (UHI) that cause problems and generate additional costs. But now, the lessons of generations of horticulturalists are being beneficially applied to the city. Planners and architects are focusing on climatically responsive urban design to counter or eliminate undesirable microclimates and nurture conditions that provide a healthier environment.

What’s up with the weather?

A microclimate is defined as any area where the climate differs from the surrounding area. Microclimates occur naturally and can be quite small. They can also be quite large. For instance, a city creates its own climatic patterns, and the larger the urban area, the more significant these will be.

A large urban microclimate can not only affect temperatures, but also rainfall, snowfall, air pressure, and wind. That means that it can increase the frequency of fog, the intensity of storms, the concentration of polluted air, and how long that bad air remains in the city.

Unintentional urban microclimates

Several factors go into creating unhealthy urban microclimates. Human-generated heat is a big part of it and much of that is caused by things like internal combustion car engines that use fossil fuels. Cars also add pollutants and humidity to the air. All of the heat-retaining paved space needed for cars simply makes matters worse.

Poor building construction and design also play a part, specifically wasteful energy consumption, shoddy insulating materials, and inefficient building management practices. And short-sighted urban planning of the height and arrangement of buildings can create stifling canyons of urban heat.

Feeling the heat around the world

Undesirable urban microclimates are a global phenomenon. In Atlanta, the number of thunderstorms rises in line with increases in road traffic. In the 1950s, London’s naturally occurring fog became denser and more polluted by the increase in car traffic and coal-fired energy emissions.

The microclimate most people think about is the urban heat island (UHI). In Melbourne, the temperature is 1.13°C higher than the surrounding less-urbanized areas. And average temperatures in Tokyo have risen by 3°C over the past century, while only rising 1°C for the country as a whole. These higher temperatures then create a ripple effect on air movements.

And they’re expensive: the UHI of Los Angeles generates additional energy costs of $100 million per year.

Taking responsibility for the weather

Architects, builders, and planners are now actively reshaping their role in the creation of urban microclimates. One way is to simply reduce unintended harmful effects. Better insulation and building management can reduce the leakage of a building’s heat while passive heating and cooling techniques can reduce the amount of heat generated by buildings.

Greater energy efficiency has an obvious benefit as well. IoT-linked digital sensors more effectively monitor energy needs with immediate effect. Net-zero technologies reduce the energy load, and net-positive technologies like the elevators from TK Elevator at One World Trade Center in New York actually produce more energy than they use through regenerative drives.

From weatherman to weather maker

The other way to think about an urban microclimate is as something that is useful. The shadows of tall buildings or skybridges offer welcome shade and cooling for cities in very hot places, and even urban heat islands might provide a benefit in extremely cold climates.

A lot of creative thinking concerns proactively shaping microclimates that are pleasant, helpful, and sustainable. Trees, parks, and greenbelts help cool cities, as well as providing other benefits to residents. Rooftop gardens and planted walls are attractive, and insulate buildings while cleaning the air.

Generally speaking, builders and planners are now combining energy efficient and sustainable technologies with a heightened sense of how each building affects its surroundings. This holistic, yet tailored approach reflects the growing awareness that there is never a standard solution to the challenge of making cities the best places to live.

More cities – weather permitting

Billions of people already live in cities, and the UN estimates 80% of the world’s population will live in urban areas by 2025. To help ensure the comfort and health of urban residents, architects, urban planners, and other decision-makers are increasingly thinking about city microclimates in new ways.

Sustainable practices, green spaces, and greater energy efficiency in buildings and urban infrastructure will help and ensure that our cities offer a healthy climate for work and play.

Image Credits:

Smog Shanghai, photo by Holger Link, taken from unsplash.com

Lightning, photo by Yarenci Hdz, taken from unsplash.com

Fire, photo by Michael Held, taken from unsplash.com